Daal Recipe

To my friends, housemates and colleagues who have had thoughts about my traditional daal recipe. Here’s an honest and detailed description in hope that you too might enjoy this staple cuisine of South Indians to your hearts’ content.

__

First, soak Masoor daal in hot water. You can use as much dal as you like but be mindful that the amount of boiled lentil will double in portion. Masoor daal is thinner that other lentils and doesn’t take long to cook. It can become very creamy in a short time if you prefer it mushy. Let it soak for couple of minutes letting debris float on top. Rinse the daal. Put the daal – now softer – into a non-stick pan. Pour in water. You can always pour more water later. Turn the heat on high and cook the daal till it reaches the desired consistency. Constantly stir the daal if you don’t have a pressure cooker. You’ve moved to London, leaving behind your mother’s traditional Indian cookware. When the daal has become mushy, turn off the heat and set it aside.

Now prepare the spices and ingredients for sautéing. Dice one large onion. Dice two green chilies… one chili… maybe just a half a chili. Peel and grate some garlic and some ginger. Grate them with a cheese grater. My mother would use garlic and ginger paste, but we can’t be bothered by that. Gather the spices that we need to later add to the sauté. At this stage, I would highly recommend opening the garden door, putting the fan on maximum and closing the kitchen door. I would also take a lid to cover the pan.

Add vegetable oil to the pan that should be on medium heat. Drop in some pinches of black mustard seeds and a single crushed red dried chili. Maybe it’s better to avoid that. Yes, avoid that as we’ve already cut green chilies. Add some pinches of fennel seeds. Once the mustard seeds start to pop, add in the sliced onions followed by the green chili. Beware the mustard seed will pop all over but the worst thing that will happen is it will release oils. The mustard seeds oil and the chili oil will interact with the heated vegetable oil. This interaction will be highly noticeable as the kitchen will become engulfed in a smell unknown to you. As a warning: this will make you uneasy indefinitely. Your eyes will water. Your lungs will give signals to your throat to cough. You will cough. You will want to leave the kitchen and wonder if this is even worth it. I would add the lid to the pan in hopes of containing the smell. It will travel through the closed door and to the living room. It will travel downstairs, upstairs and to the attic. The neighbors will smell it. God forbid you cook this during a weekend evening when your housemates decide to hit the club in their sleek clothes and covered in some generic cheap perfume. Of course you don’t tell them it’s a horrible generic smell. If they are about to leave for a date on this time, they are going to wish you returned back to India in the next second, almost like when a magician releases smoke and presto! Of course, they’ll want you to take with you the smell which they can’t figure out what it is.

When the onion starts to soften, add the grated ginger and garlic. Cover the pan with the lid again. When you open the lid to stir or add more ingredients, do so very quickly and scarcely as to avoid the smell leaving the pan. Let the ginger and garlic cook and interact with now somewhat caramelized onions. Don’t burn it. Keep on stirring. But always make sure you do it quickly and then cover the pan with lid. Don’t forget that.

Now prepare the spices and ingredients for sautéing. Dice one large onion. Dice two green chilies… one chili… maybe just a half a chili. Peel and grate some garlic and some ginger. Grate them with a cheese grater. My mother would use garlic and ginger paste, but we can’t be bothered by that. Gather the spices that we need to later add to the sauté. At this stage, I would highly recommend opening the garden door, putting the fan on maximum and closing the kitchen door. I would also take a lid to cover the pan.

Add vegetable oil to the pan that should be on medium heat. Drop in some pinches of black mustard seeds and a single crushed red dried chili. Maybe it’s better to avoid that. Yes, avoid that as we’ve already cut green chilies. Add some pinches of fennel seeds. Once the mustard seeds start to pop, add in the sliced onions followed by the green chili. Beware the mustard seed will pop all over but the worst thing that will happen is it will release oils. The mustard seeds oil and the chili oil will interact with the heated vegetable oil. This interaction will be highly noticeable as the kitchen will become engulfed in a smell unknown to you. As a warning: this will make you uneasy indefinitely. Your eyes will water. Your lungs will give signals to your throat to cough. You will cough. You will want to leave the kitchen and wonder if this is even worth it. I would add the lid to the pan in hopes of containing the smell. It will travel through the closed door and to the living room. It will travel downstairs, upstairs and to the attic. The neighbors will smell it. God forbid you cook this during a weekend evening when your housemates decide to hit the club in their sleek clothes and covered in some generic cheap perfume. Of course you don’t tell them it’s a horrible generic smell. If they are about to leave for a date on this time, they are going to wish you returned back to India in the next second, almost like when a magician releases smoke and presto! Of course, they’ll want you to take with you the smell which they can’t figure out what it is.

When the onion starts to soften, add the grated ginger and garlic. Cover the pan with the lid again. When you open the lid to stir or add more ingredients, do so very quickly and scarcely as to avoid the smell leaving the pan. Let the ginger and garlic cook and interact with now somewhat caramelized onions. Don’t burn it. Keep on stirring. But always make sure you do it quickly and then cover the pan with lid. Don’t forget that.

At this moment. It’s vital to note and take precaution so to not let your feelings be hurt. Carla will open the kitchen door. She will not step inside the kitchen and exclaim: “What are you making? The whole house smells!” You should apologize and try not to feel inferior. Carla is an European descendent from Chile. Her seasoning includes salt and pepper at minimal. She simply doesn’t know, and it’s not right to judge her for her lack of knowledge. You think about taking all that precaution — opening back door, turning the fan to maximum, covering pan with a lid and getting condensation and water in your sautéing only to feel like you’re a “bloody typical Indian.” Carla asks: “What spices are you using?” Lie and tell her “chili, turmeric and Garam Masala.” You haven’t added the spices yet.

When Carla leaves, you close the kitchen door, and relieve in the joy that she left so you don’t feel shame. At least not directly. Open the lid on pan as it should be time to add the spice powders. Oh, but before you do that, quickly grab a tomato, wash it and dice it and add it to the pan. Give it a stir. Once the tomato looks soft and mushy, add in a moderate level of coriander powder, followed by cumin powder. I put in equal amount of each. I love the smell of cumin. It reminds me of my mother’s cooking. Make sure to add in a little more than a pinch of turmeric or at least till the desire amount of rich yellow colour you’d like your daal to be before stirring the pan. You don’t add Garam Masala. Stir the spices and let them cook for a minute. The spices don’t really submerge the kitchen in that same heavy smell when the mustard seeds and chili infuse with oil. Feel free to sigh. You deserve it.

Now it’s time to add in the daal to the pan with the spices all prepared. Add a bit of water and make sure to scoop up all the little daal as some might be stuck to the pan. Pour in some water, depending on how thick or thin you want your daal to be. Are you going to be having the daal with rice or naan bread? You can have daal with couscous or millet too, like what I have seemed to be doing since moving to London. My South Indian family has daal with basmati, yogurt and pureed kale or spinach with poppadums. Add a small amount of coconut powder and let the daal bubble. Turn off the heat and add in fresh cilantro leaves.

Now after all this dedication, pain and tears (mostly if not all emotional), prepare to lie to curious gawkers who have never seen daal or aren’t familiar with this dish. Don’t overthink it and tell them yes this is a traditional recipe. They will ask: “What about ghee?” Inform you that you haven’t used it in the recipe. You have also omitted curry leaves, but don’t tell them about that. Tell them you don’t like the smell of ghee.

There you have it — South Indian daal.

When Carla leaves, you close the kitchen door, and relieve in the joy that she left so you don’t feel shame. At least not directly. Open the lid on pan as it should be time to add the spice powders. Oh, but before you do that, quickly grab a tomato, wash it and dice it and add it to the pan. Give it a stir. Once the tomato looks soft and mushy, add in a moderate level of coriander powder, followed by cumin powder. I put in equal amount of each. I love the smell of cumin. It reminds me of my mother’s cooking. Make sure to add in a little more than a pinch of turmeric or at least till the desire amount of rich yellow colour you’d like your daal to be before stirring the pan. You don’t add Garam Masala. Stir the spices and let them cook for a minute. The spices don’t really submerge the kitchen in that same heavy smell when the mustard seeds and chili infuse with oil. Feel free to sigh. You deserve it.

Now it’s time to add in the daal to the pan with the spices all prepared. Add a bit of water and make sure to scoop up all the little daal as some might be stuck to the pan. Pour in some water, depending on how thick or thin you want your daal to be. Are you going to be having the daal with rice or naan bread? You can have daal with couscous or millet too, like what I have seemed to be doing since moving to London. My South Indian family has daal with basmati, yogurt and pureed kale or spinach with poppadums. Add a small amount of coconut powder and let the daal bubble. Turn off the heat and add in fresh cilantro leaves.

Now after all this dedication, pain and tears (mostly if not all emotional), prepare to lie to curious gawkers who have never seen daal or aren’t familiar with this dish. Don’t overthink it and tell them yes this is a traditional recipe. They will ask: “What about ghee?” Inform you that you haven’t used it in the recipe. You have also omitted curry leaves, but don’t tell them about that. Tell them you don’t like the smell of ghee.

There you have it — South Indian daal.

In 2014, I participated in DesignInquiry in Maine. DesignInquiry is a non-profit educational organization devoted to researching design issues in intensive team-based gatherings.

Inspired by the year's theme, access, my contribution was a guide to image-making workshop inspired by the Vishnu Dharmottara.

Vishnu Dharmottara is a good vehicle for making inquirers aware of their own understanding or design assumptions as they follow a written rule set to depict the described gods and goddesses.

Vishnu Dharmottara is an extremely detailed and highly sophisticated structured treatise that prescribes rules on Indian painting and image-making of Gods and Goddesses. It deals not only with the religious aspect, but also, and to a far greater extent, with its secular employment. The text follows the traditional pattern of exploring the various dimensions of a subject through conversations that take place between a learned master and an ardent seeker eager to learn and understand. The Vishnu Dharmottara prescribes textual narration but is void of visual guidance. The Vishnu Dharmottara is a compilation of multiple sources and dates back to 6th century A.D. The translation by Dr. Stella Kramisch in 1928 represents the earliest comprehensive account of the theory of image-making in India.

Vishnu Dharmottara argues for abstract and realistic representation, artistic inspiration and the image’s essence. The ardent seekers—the graphic design students—would employ these rules to construct images of the described gods/goddesses for their visual interpretation.

The transmission of imagination into a visual is an intrigue. As designers and educators we are intrigued by how our imagination or visualization of a particular project is translated in design. We imagine the composition with a particular layout, typography, colour, etc. but when transferred from imagination to paper, screen, or model, the outcome can be quite different from what we expected. The discourse between the King and the Sage is an exploration between that dialogue between imagination and visualization. The instructions outlined in the text are the practice of making imagination visible, and allows the image-maker to increase their own awareness and understanding of visuals. The Vishnu Dhamottara enables imagination by prescribing the form and keeping the rest of the representation vague. This amount of prescription leaves the image-maker to imagine and have their inspiration, creativity and intuition complete the image.

Vishnu Dharmottara is a good vehicle for making designers and students aware of their own understanding or design assumptions as they follow a written rule set to depict the described gods and goddesses. The written rules set to depict the described gods and goddesses is a great frame of reference. The gods and goddesses offer a wide range of exploration. Creating these images allows the

Vishnu Dharmottara argues for abstract and realistic representation, artistic inspiration and the image’s essence. The ardent seekers—the graphic design students—would employ these rules to construct images of the described gods/goddesses for their visual interpretation.

The transmission of imagination into a visual is an intrigue. As designers and educators we are intrigued by how our imagination or visualization of a particular project is translated in design. We imagine the composition with a particular layout, typography, colour, etc. but when transferred from imagination to paper, screen, or model, the outcome can be quite different from what we expected. The discourse between the King and the Sage is an exploration between that dialogue between imagination and visualization. The instructions outlined in the text are the practice of making imagination visible, and allows the image-maker to increase their own awareness and understanding of visuals. The Vishnu Dhamottara enables imagination by prescribing the form and keeping the rest of the representation vague. This amount of prescription leaves the image-maker to imagine and have their inspiration, creativity and intuition complete the image.

Vishnu Dharmottara is a good vehicle for making designers and students aware of their own understanding or design assumptions as they follow a written rule set to depict the described gods and goddesses. The written rules set to depict the described gods and goddesses is a great frame of reference. The gods and goddesses offer a wide range of exploration. Creating these images allows the

image-maker to not only imagine and interpret the text but also encourages self-reflection. We can reflect on our own image-making processes, and consider the role of faith and nature in our value systems. The Vishnu Dharmottara is an excellent vehicle for making graphic designers aware of their own understanding and design assumptions. Applied in design education, Vishnu Dharmottara will not only inspire another process of image-making but also continue dialogue on graphic design’s important relationship to interculturality.

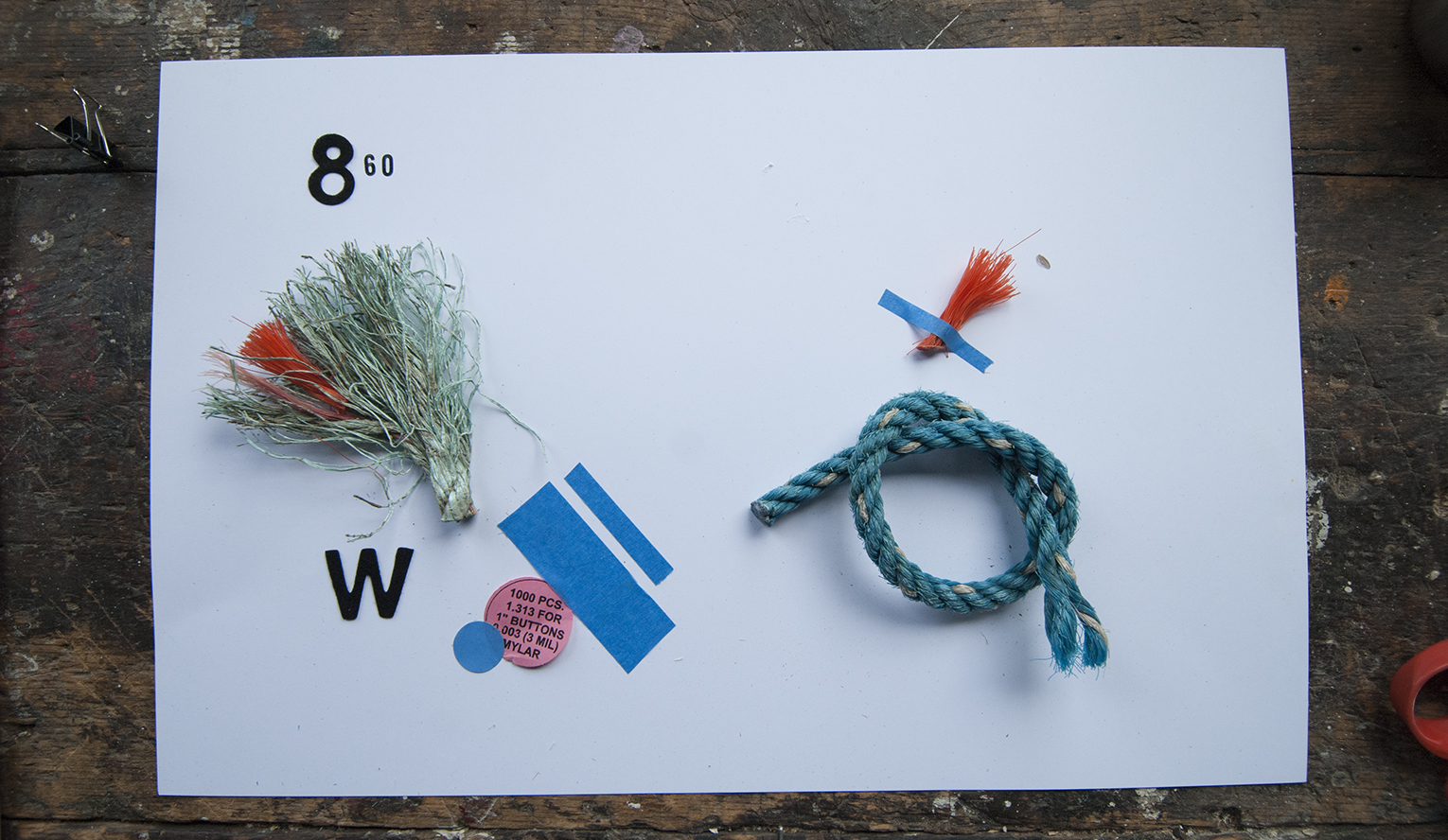

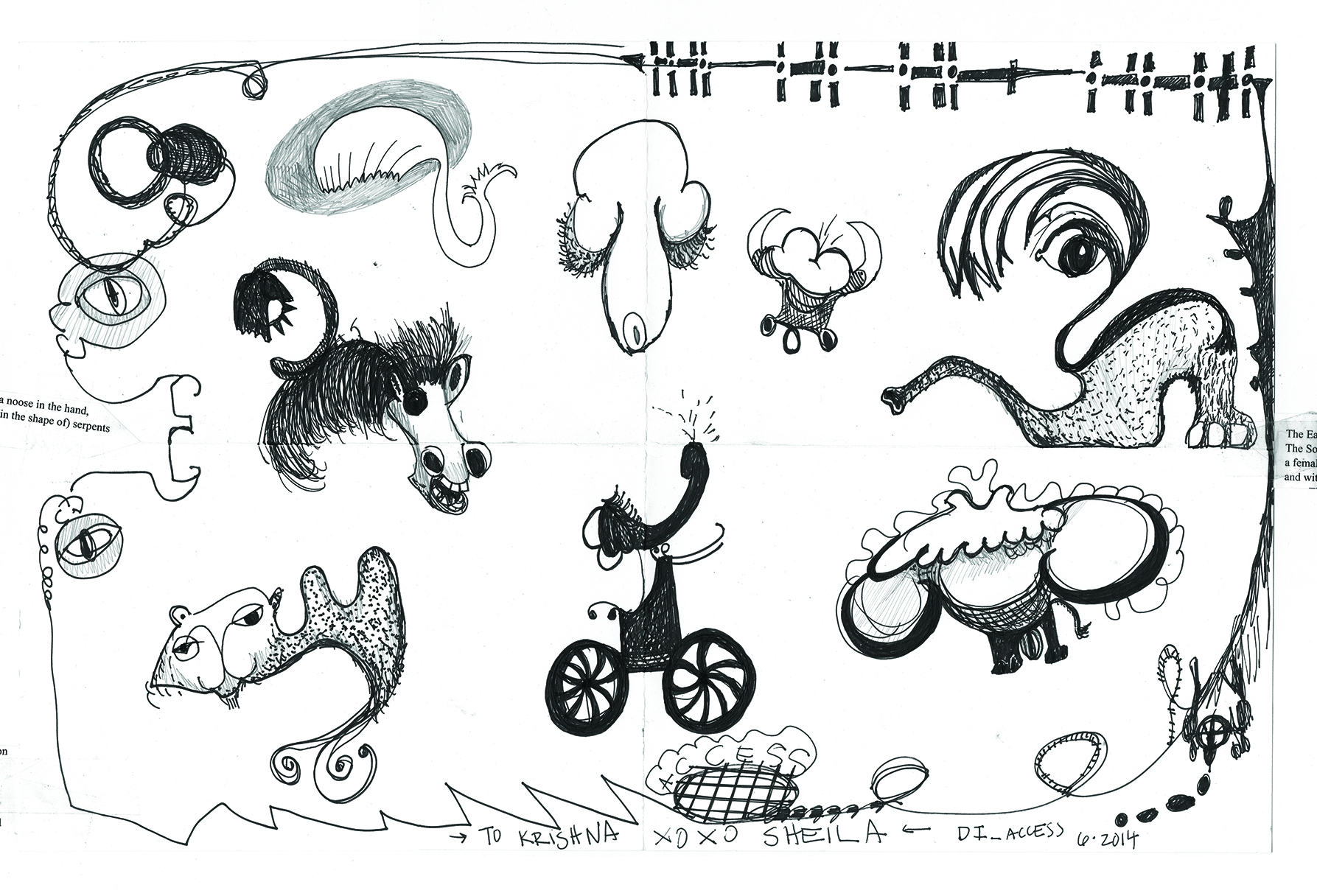

The exercise was to interpret the following description of the 'Directional Gods and Goddesses,' according to the individual's concept of abstract using materials found on the Island. It is interesting to note the varied interpretations, which essentially portrayed the individual's profession as image-makers.

Directional Gods and Goddesses on Part III, Ch. 73, Verses 1-51 are described as :

The Eastern direction should be a lady red and seated on an elephant. The South-eastern is a bulky maiden of the colour of the lotus, seated on a female elephant. The Southern should be yellowish, placed on a chariot and with youth (fully) attained.

The South-western belonging to Varuna is dark-yellow and seated on a camel. The West is dark, destitute of youth and seated on a horse.

Oh delighter of the Yadus, Vadava (the NW) is blue and with hair almost grey. The North is white, old and borne by a man .

The North-east should be very old, white, and seated on a bull. The lower region is similar to the earth and the upper region is suspended in the sky.

The ever-present Kala should be shown with a noose in the hand, terrific, with a large face having hairs on the body (in the shape of) serpents and scorpions.

The following images are some of those interpretations by designers, educators, writers and image-makers:

The exercise was to interpret the following description of the 'Directional Gods and Goddesses,' according to the individual's concept of abstract using materials found on the Island. It is interesting to note the varied interpretations, which essentially portrayed the individual's profession as image-makers.

Directional Gods and Goddesses on Part III, Ch. 73, Verses 1-51 are described as :

The Eastern direction should be a lady red and seated on an elephant. The South-eastern is a bulky maiden of the colour of the lotus, seated on a female elephant. The Southern should be yellowish, placed on a chariot and with youth (fully) attained.

The South-western belonging to Varuna is dark-yellow and seated on a camel. The West is dark, destitute of youth and seated on a horse.

Oh delighter of the Yadus, Vadava (the NW) is blue and with hair almost grey. The North is white, old and borne by a man .

The North-east should be very old, white, and seated on a bull. The lower region is similar to the earth and the upper region is suspended in the sky.

The ever-present Kala should be shown with a noose in the hand, terrific, with a large face having hairs on the body (in the shape of) serpents and scorpions.

The following images are some of those interpretations by designers, educators, writers and image-makers:

Gail Swanlund

Margo Halverson

Joshua Unikel

Sarah Shoemake

Arzu Ozkal

Emily Luce

Steve Bowden and Nick Davis

Sheila Pepe

Joshua Singer